|

From: The Canadian Encyclopedia - Playing Card

Money

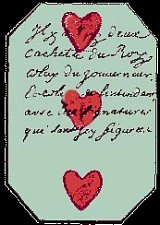

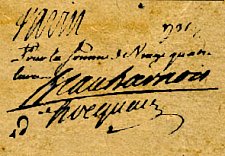

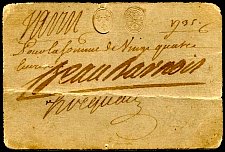

"The administration of New France counted on the arrival of cash from

France in order to pay civil servants, suppliers, soldiers and clerks.

There was confusion if the ship did not arrive until the end of the

season, and even more if it did not come at all. In 1685 Intendant

Demeulle invented a type of paper money with the purpose of meeting the

expenses. He printed various face values on playing cards and affixed

his seal to them. When the king's ship arrived, he redeemed this "card

money" in cash. This system was brought to an end after 1686, but it was

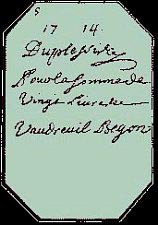

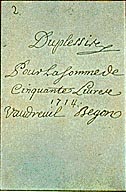

necessary to return to it during the period 1689-1719. In 1714, card

money to a value of 2 million livres was in circulation, some cards

being worth as much as 100 livres.

The King later returned to using card money in

1729 because the merchants themselves demanded it, this time using white

cards without colours, which were cut or had their corners removed

according to a fixed table. The whole card was worth 24 livres (which

was the highest sum in card money); with the corners cut off, it was

worth 12 livres; etc. In the 18th century card money was not the most

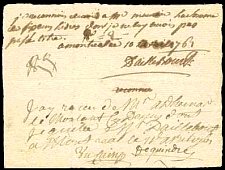

important form of paper money. There was the certificat

(certificate), a certified sum given to the supplier by the storekeeper.

The ordonnance, a promissory note, was signed by the intendant on

a printed form, and like cards and certificates, was redeemable by a

lettre de change (bill of exchange) on the Naval Treasury. Finally,

there was the lettre de change, or traite, used between

private citizens to avoid a cash transfer, which the state also used,

particularly to redeem paper money. After the Conquest Canadians still

held some 16 million livres in paper money, of which only 3.8% was in

card money."

Gouvernor General: 10

Mar 1685 - 1 Aug 1685 Jacques de Meulles, seigneur

de La Source (acting)

From this time on the curious practice of using regular troops

as a civilian labour force, and the civilian militia for military operations,

was to endure. Once the harvest was in, however, the habitants did not need this

labour and de Meulles had to resort to another expedient to pay the troops. He

deserves a good deal of credit for the imaginative and ingenious device that he

now inaugurated: the issuing of the first paper money to circulate in North

America. He took packs of playing cards, of which there seems to have been a

plentiful supply, and made money of them by writing an amount on the back, with

his signature. He issued an ordinance declaring that

the cards would be redeemed as soon as the ships arrived from France with

the annual supply of funds; meanwhile they had to be accepted at face value.

This paper money had greater success and a longer life than de Meulles could

ever have anticipated. There was always a shortage of currency in the colony

(beaver skins were much used in lieu of it), and the card money filled a real

need. In the years that followed, no sooner was the card money redeemed than

necessity, or convenience, caused it to be reissued. The colony thus had a

unique but viable monetary system of its own; one that, on the whole, served it

well."

|

Cite This Article

W. J. Eccles,

“MEULLES, JACQUES DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol.

2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 31, 2013,

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meulles_jacques_de_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for

footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style

(16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

Permalink: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meulles_jacques_de_2E.html |

| Author of Article: |

W. J. Eccles |

| Title of Article: |

MEULLES, JACQUES DE |

| Publication Name: |

Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol.

2 |

| Publisher: |

University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication:

|

1969 |

| Year of revision: |

1969 |

| Access Date: |

July 31, 2013 |

Gouvernor General: Jacques-René de Brisay,

marquis de Denonville, 1.8.1685 - 12.8.1689

The Sovereign Council as a Superior Court:

The Sovereign Council acted

as the court of appeal for decisions made in the lower courts in New France. Any

criminal conviction could be appealed to the Council.[22]

There was some hope in a more favourable outcome, as the attorney general who

sat on the Council was the only official in New France required having formal

university legal training.[23]

The Sovereign Council could

also amend verdicts without overturning convictions. In 1734, an African slave

burned her owner’s home in protest. The local magistrate ordered the accused to

be burned alive, but the Council intervened and commuted the punishment to death

by hanging.[24]

The crimes prosecuted by the

colonial judicial system, and, by extension, the Sovereign council, were

diverse, although extra weight was given to crimes that undermined France’s

colonial interests. An increasing problem was acts against the crown including

forgery, where subjects created counterfeit money by modifying their playing

cards (also a source of money at the time), and this comprised approximately 17%

of all cases in the 18th century

HISTORY OF

MONEY IN CANADA - New France (ca. 1600-1770)

The introduction of card

money In 1685,

the colonial authorities in New France found themselves short of funds. A

military expedition against the Iroquois, allies of the English, had gone badly,

and tax revenues were down owing to the curtailment of the beaver trade because

of the war and illegal trading with the English. Typically, when short of funds,

the government simply delayed paying merchants for their purchases until a fresh

supply of specie arrived from France. But the payment of soldiers could not be

postponed. Having exhausted other financing avenues and unwilling

to borrow from merchants at the terms offered, Jacques de Meulles, Intendant of

Justice, Police, and Finance came up with an ingenious solution—the temporary

issuance of paper money, printed on playing cards. Card money was purely a

financial expedient. It was not until later that its role as a medium of

exchange was recognized. The first issue of card money occurred on 8 June 1685

and was redeemed three months later. In a letter dated 24 September 1685, to the

French Minister of the Marine justifying his action, de Meulles wrote, I

have found myself this year in great straits with regard to the subsistence of

the soldiers. You did not provide for funds, my Lord, until January last. I

have, notwithstanding, kept them in provisions until September, which makes

eight full months. I have drawn upon my own funds and from those of my friends,

all I have been able to get, but at last finding them without means to render me

further assistance, and not knowing to what Saint to say my vows,money being

extremely scarce, having distributed considerable sums on every side for the pay

of the soldiers, it occurred to me to issue, instead of money, notes on cards,

which I have cut in quarters . . . I have issued an ordinance by which I have

obliged all the inhabitants to receive this money in payments, and to give it

circulation, at the same time pledging myself, in my own name, to redeem the

said notes (Shortt 1925a, 73, 75). These cards were readily

accepted by merchants and the general public and circulated freely at face

value. Card money was next issued in February 1686. The authorities in France

were not pleased, however. In a letter to de Meulles dated 20 May 1686, they

wrote, He [His Majesty] strongly disapproved of the expedient which he

[de Meulles] has employed of circulating card notes, instead of money, that

being extremely dangerous, nothing being easier to counterfeit than this sort of

money. Letter to de Meulles, 20 May 1686 (Shortt 1925a, 79)7

Notwithstanding this admonition, the colonial authorities reissued card money in

1690 because of another revenue shortfall. Again, the cards were redeemed in

full. However, given their wide acceptance as money, asignificant proportion was

not submitted for redemption and remained in circulation, allowing the

government to increase its expenditures. The following year, with yet another

issue of card money, the Governor, Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac,

acknowledged the useful role that card money played as a circulating medium of

exchange in addition to being a financing tool (Shortt 1925a, 91). While the

authorities in France worried about the risk of counterfeiting and a loss of

budgetary control, the colonial authorities successfully argued that the cards

served as money in Canada just as coin did in France. Moreover, the Kingdom of

France derived benefits from the circulation of cards, since the King was not

obliged to send coins to Canada risking loss “either from the sea or from

enemies.” Reflecting the mercantilist sentiments of the time, they less cogently

argued that if coins were to circulate in Canada, some would be used to buy

supplies from New England, resulting in “considerable injury to France by the

loss of its coinage and the advantage which it would produce among her

enemies.”8 The concerns of the authorities in France were not entirely

misplaced. In the early 1690s, the first signs of inflation began to be noticed

as a result of the excessive issuance of card money. Although cards continued to

be redeemed in full upon presentation, the stock of card money increased over

time faster than demand, causing prices to rise. With the finances of the French

government progressively deteriorating during the first part of the eighteenth

century, owing to European wars, financial support for its Canadian colonies was

reduced. The colonial authorities in Canada consequently relied increasingly on

card money to pay their expenses. In 1717, with inflation rising sharply, it was

agreed that card money should be redeemed with a 50 per cent discount and

withdrawn permanently from circulation. At this time, Canada also adopted the

monnoye de France.

By failing to provide a replacement for card money, the unintended consequence

of this monetary reform was recession. In an attempt to remedy the situation,

copper coins were introduced in 1722, but they were not well received by

merchants. Notes issued by private individuals based on their own credit

standing also circulated as money, a practice that pre-dated this event, and

continued periodically well into the nineteenth century and, arguably, even to

the present day.10 The government, again short of funds, also issued promissory

notes called ordonnances, which began to circulate as money. In March

1729, in response to requests from the public, the government received

permission from the King to reintroduce card money. These cards would be

redeemed each year for goods or for bills of exchange11 drawn on funds

appropriated for the support of the colony that would be payable in cash in

France.12 The cards, which were strictly limited, were legal tender for all

payments and replaced the ordonnances in circulation. Confidence in this

new card money was initially high. With the supply limited and convertible into

bills of exchange payable in France, the cards were an economical alternative to

the transfer of specie across the Atlantic. Gold and silver began to accumulate

in New France and stayed. The government, however, remained financially

constrained and began to rely again on ordonnances and another form of

Treasury notes called acquits to fund its operations. With issuance

tightly controlled, card money traded at a premium for a time as the government

increased its issuance of Treasury notes to pay for its operations. But as

French finances deteriorated and the redemption of Treasury notes was repeatedly

postponed, trust in card money was also undermined.

By the early 1750s, the distinction between card money and Treasury notes had

largely disappeared, and by 1757, the government had discontinued payments in

specie; all payments were made in paper. In an application of Gresham’s Law—bad

money drives out good—gold and silver were hoarded and seldom, if ever, used in

transactions.

A rapid increase in the amount of paper in circulation during the late 1750s

resulting from the mounting costs of the war with the British, declining tax

revenues, and rampant corruption, led to rapid inflation. In a letter dated 12

April 1759, the Marquis de Montcalm noted that provisions absolutely necessary

to life, cost eight times more than when the troops arrived in 1755. . . . The

colonist is astounded to see the orders of the Intendant, in addition to the

cards, circulating in the market to the extent of thirty millions. People, fear,

I think without foundation, that the government will make a sort of assignment

or authorize a depreciation. This opinion induces them to sell and speculate at

an extravagant scale and price. . . .(Shortt 1925b, 889, 891). On 15 October

1759, the French government suspended payment of bills of exchange drawn on the

Treasury for payment of expenses in Canada until three months after peace was

restored.13 Paper money traded at a sharp discount. Immediately following the

British conquest in 1760, paper money became all but worthless. But business in

Canada did not come to a halt. Gold and silver that had been hoarded came back

into circulation.

Settlement of the paper obligations issued by the colonial authorities in Canada

was included in the Treaty of Paris, signed in February 1763, which ended the

war between Great Britain and France.14 In anticipation of a favourable

settlement, speculators bought card and other paper money. British merchants

also began to accept the paper, although at a discount of 80 to 85 per cent.

Governor Murray, in charge of British troops in Quebec, recommended that

Canadians hold onto their paper in the hope of a better deal.15 After extensive

negotiations over the next three years, the French government finally agreed to

convert card money and Treasury paper into interest-earning debentures on a

sliding scale depending on the type of notes and their age, with discounts

ranging from 50 per cent to 80 per cent. Typically, older notes were given a

smaller discount. However, with the French government essentially bankrupt,

these bonds quickly fell to a discount and, by 1771, they were worthless. |

![]()