|

. |

|

. |

|

|

|

|

Home>Resources>Article

Index>Colombia Index>Bank

of Antioquia, Part II |

Next Articles> |

|

. |

|

|

COLOMBIA ARTICLES |

|

|

BANK OF ANTIOQUIA,

PART II

Posted: October, 2000

As I mentioned in the first part, the business of gold was the principal economic activity of the banks in Antioquia but not the only one.

Onehundred eighty-day loans were the norm of the Bank of Antioquia, and in general also in the banks of Medellin. This was due to the lack of liquidity that governed it. In this way it guaranteed the prompt return of money with earnings and interest. Except for a few exceptions, and when the bank enjoyed good liquidity, it granted credit on a longer time period, but none of the loans exceeded a year in length.

For the period in Antioquia before the appearance of banks, interest rates fluctuated between 8% and 12% annually. the commercial houses in Medellin, such as Vicente B. Ville, Botero Arango and Sons, and Restrepos and Company, among others governed these rates. Usury rates varied between 18% and 20% among private load companies.

When the bank began operations, its rates dropped to 6%. Logically, this move awakened antipathy among the lenders and businessmen of the community who, accordingly, saw their earnings diminish. This sentiment was passed on upon seeing the quality and quantity of the securities and guarantees required by the bank to carry out the payment of the loans. The 6% rate was maintained for four years through a decision of the directive council up to December 1875. At the beginning of January 1876, the rate was increased to 8% to 1883, when,

at the beginning of that year, it went up to 12% annually.

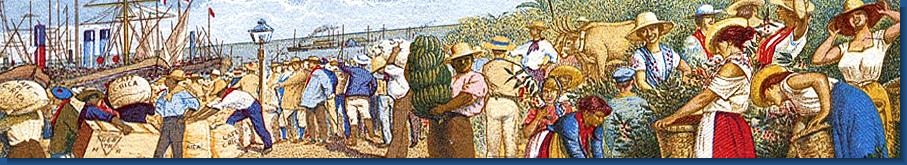

As was already mentioned, the Sovereign State of Antioquia was the principal beneficiary of the bank loadns, followed by the Antioquira railroad. Except for a few loans to mining companies, the commerical houses that would provide imported merchandise to the habitants of Antioquia would utilize the majority of the loans in Medellin. It definitely was the lucrative business at the end of the 19th Century.

A curious fact happened in 1879 when the first assault took place on a bank in Antioquia. It was carried out by General Rengifo who sacked the bank and did not leave a cent in the vault on the pretext that it was a Spanish bank.

|

Liquidation of the Bank

To exactly speak of the when and why of the liquidation of the bank is very difficult because all of the banks archives disappeared, and one can only speculate about these facts.

Rafael Nunez's project of creating a National Bank began on January 1, 1881. This bank issued banknotes until 1885 when the war put an end to the bank's part in issuing banknotes and economic chaos erupted. Upon seeing this, the government decreed the forced circulation of the banknotes and tried to assure itself that this inconvertible paper money that did not have any metallic economic backing might keep on circulating. These stated means forced individuals as well as the private banks to receive from their creditors

these banknotes. With Antioquia having the healthiest and strongest economy in the country, everyone laughed at don Rafael. Because of this, the government issued decree 104 in 1886, which changed the monetary system of the country.

In the decree it was ordered that beginning on May 1st of this year the monetary unit and money on account for all legal transactions in the entire Colombian territory would he a peso note issued by the National Bank. This banknote would substitute in this way all money and existing metal standards. All of this was backed only by the good faith and responsibility of the government.

In Antioquia laughter passed for nervious laughter for the moment, but after

consultations and meetings of bankers and businessmen of Antioquia, anarchy and

general disobedience were encouraged for these measures. Many banks preferred to shut their doors rather than receiving "paper from those guys," and those who did not close their doors never accepted the banknotes. In Antioquia, the private banks -- in spite of constant threats and visits by the government -- continued to issue their own banknotes, and business received them as a bonus over those of the National Bank. The National Bank notes were accepted as fractional currency of lesser value, and businesses concelled their taxes with these notes. The most rebellious and warlike fighter against Nunez's

system was the Banco del Oriente that circulated their own notes in Antioquia even after the founding of the Bank of the Republic.

Apparently, the Bank of Antioquia went bankrupt in 1893 in great part because one of its founding partners had been the Sovereign State of Antioquia. But at the date of liquidation it had not been a State much less Sovereign, but, on the contrary, it had depended politically and economically on a central government in Bogota. It saw itself obliged to observe the means that were being taken there. Because of this and without wanting to, the state was going against the rest of the members of the Directive Council.

Its banknotes kept on circulating for many years. They were backed by an ex-partner of the bank, don Jose Maria Melguizo. In 1900 they were assimilated by money drafts and would circulate for many more years.

|

THE BANKNOTES

A real puzzle was that of trying to decipher the issues of the bank. First, no written register remains since all of the archives disappered. After much investigation only the constitution of the corporation succeeded in being known. Apparently it is the only piece that survived negligence and time.

With respect to the dates of issues, they were even more difficult because although the banknote was already printed, it ws issued at the moment that the customer needed it, and the date, day, and month were written by hand. Only the three first digits of the year were pre-printed. In these cases one had to be like St. Thomas; that is, you have to see it to believe it. I wil only describe what I know and what I have had in my hands.

10 Centavos: Printed by: Tipografia Central Medellin. Size: approx: 7.3 x 4.3 centimeters. Issued as a draft under the responsibility of Jose Maria Melguizo who signed them as proprietary manager on the front and who was the successor to the bank after its liquidation. I am familiar with this in the first, second and third class, all with legends and symbols in black ink with the exception of the number of the series and the signature of don

Jose Maria which are in red ink all over a line screen in the front. On the right side of the banknote (on the left for whoever looks at it) the number ten appears on a black line screen; it occupies almsot a third of the small banknote.

In the catalog of Yasha Beresiner and in the specialized catalog of Albert Pick, reference is made to a peso banknote, issued on January 2, 1885 and printed in Medellin. I am not familiar with it, and if some had it, I would appreciate if he could communicate with me so that I could photograph it.

With respect to the rest of the banknotes, those interested can observe them in the Pick catalog. I say that they can see them there because discovering them would be very significant. These banknotes are in 1, 2, 5 and 10 pesos. With respect to the varieties of these notes, I can mention the following:

All of the banknotes were printed by Perkins, Bacon, & Co. in London, England, specimens of the four banknotes are known. All of the inks and back lines are black and correspond to the first edition of the seventies. No specimens of the edition of the eighties are known to exist. First edition 187_; second edition 188_.

The back of all of these is exactly equal and consists of a woven oval where the words Bank of Antioquia are read. This is superimposed with two small ovals, each one with a number in the center that indicates the face value. All of this occupies approximately a third of the banknote in the center, leaving a great part of the banknote blank. The color of the peso bill of the first series is all black, and in the second series it is green and orange.

The two-peso note is red and black in the first series and completely blue in the second. The five-peso note is black and orange in both series. The ten-peso note is brown in the first series and blue in the second.

Regarding the issuing dates, there can be hundreds of them since the bank issued them at the moment that the customer needed them; therefore, there can appear banknotes with a day's difference in their issue. There even might have been requested more exact data, such as the time of day, for example. We find banknotes issued with one-half, one or two hour differences. Because of the previous reason, I am advising collectors so as not to drive themselves crazy looking for the dates of these notes because almost surely they would

be armed with real almanacs of notes which would only lack Sundays and holidays.

The 1, 2, 5 and 10 Peso notes are known to be specimens issued by don Jose Maria Melguizo and were assimilated into drafts after the liquidation of the bank. These are easily recognizable by the following characteristics:

First: All correspond to banknotes without being issued in the second edition 1888_.

Second: On the front side a red seal that indicates the face value in

letters over a line screen of the same color, and this, in turn, over an original legend of the banknote that says:

|

"THE BANK OF ANTIOQUIA WILL PAY to the bearer and

on sight the quantity of FIVE PESOS this value according to the case in current money"

|

Third: The autographed signature of don Jose

Maria appears on the front side.

Fourth: An overprint in black ink is read on the backside that says:

|

"This banknote is in charge of Jose Maria Melguizo H. the successor and owner of the 'Bank of Antioquia,' it is assimilated as a draft three days seen, according to contract with the government, January 19, 1900" |

See Pick Volume One, 8th Ed., pages 514-515. Notes of the bank are listed and illustrated.

Israel Maya M.

Source: Boletin 130, Marzo de 2000, Club Natafflico Medellin.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|