|

The

year 1969 ended when we Argentines were fully aware that, in fulfillment

of a law dictated

eight months before, when 1970 began,

we would have in the country another monetary symbol. It was easy to imagine the confusion of the

people who, for many decades, handled "National Peso Money (m$n). Nevertheless, through the dictum of the aforementioned law, beginning January 1, 1970, the "peso" would be in force. eight months before, when 1970 began,

we would have in the country another monetary symbol. It was easy to imagine the confusion of the

people who, for many decades, handled "National Peso Money (m$n). Nevertheless, through the dictum of the aforementioned law, beginning January 1, 1970, the "peso" would be in force.

This new peso was quickly baptized as the "law peso" (peso ley) at the popular level. The circumstances under which the public was given this name should not lead us to think that this peso was easily accepted. Although the documents and the accounting registers should have adopted

this new denomination,

our idiosyncrasies never assimilated them, to the point that - even at the

moment that they were replaced thirteen years later - the people on the

street kept on talking in

"old" pesos (pesos viejos), although they

forcibly manipulated the notes issued at the beginning of 1970.

For a greater cultural

and idiomatic complication, the "Pesos Ley 18.188" came to be known as the

"Decree-Law 18.188/69" (Decreto-Ley 18.188/69), beginning with the restoration

in 1973 of the democratic system whose de facto type of government sanctioned

the legislation which still occupies us.

What did the  1969 monetary reform consist of? Because inflation had eroded part

of the value of the "national monetary peso" ("peso monetaria nacional"), following the French precedent, the Argentine Government decided to take two zeros off from the currency, that is to say, to divide by one hundred (100) the value of 1969 monetary reform consist of? Because inflation had eroded part

of the value of the "national monetary peso" ("peso monetaria nacional"), following the French precedent, the Argentine Government decided to take two zeros off from the currency, that is to say, to divide by one hundred (100) the value of

What did the 1969 monetary

reform consist of? Because inflation had eroded part of the value of the

"national monetary peso" ("peso monetaria nacional"), following the French precedent, the Argentine Government decided to take two zeros off from the currency, that is to say, to divide by one hundred (100) the value of

the currency and to grant a new birth to a new Peso ($1=m$n100), so that what then was valued as 10 or 50 pesos would now become 10 or 50 cents respectively.

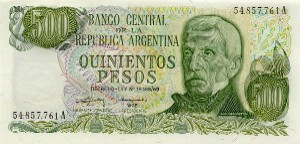

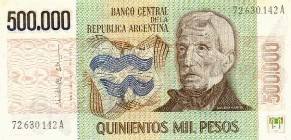

From a numismatic point of view, the new banknotes were characterized by having all the same measurements (155 x 75m m), unlike the "moneda nactional" banknotes whose size grew with its face value. It was foreseen to put into circulation notes of 1,5,10,50,100,500, and 1,000 pesos, although the inflational spiral deemed it necessary to issue face values up to 1,000,000. So that the change would not be so abrupt, the Central Bank - in a first state - overprinted in the left oval banknotes between m$n100 to 10,000 (converting them into notes from 1 to 100 "peso ley") so that the public might visualize the equivalencies. The only new banknote that hit the streets from the first moment was the one (1) peso note with the image of Manuel Belgrano. Little by little, the other denominations were incorporated, maintaining the colors of the equivalent notes from previous issues. m), unlike the "moneda nactional" banknotes whose size grew with its face value. It was foreseen to put into circulation notes of 1,5,10,50,100,500, and 1,000 pesos, although the inflational spiral deemed it necessary to issue face values up to 1,000,000. So that the change would not be so abrupt, the Central Bank - in a first state - overprinted in the left oval banknotes between m$n100 to 10,000 (converting them into notes from 1 to 100 "peso ley") so that the public might visualize the equivalencies. The only new banknote that hit the streets from the first moment was the one (1) peso note with the image of Manuel Belgrano. Little by little, the other denominations were incorporated, maintaining the colors of the equivalent notes from previous issues.

The centavos, which had fallen into disuse because of their lack of value, began to have value again, and thus official propaganda bounced back again. New coins of 1,5,10,20, and 50 centavos with the effigy of "Liberty" and impression mark 1970 would see the light of day, all of them in a circular shape. (The 5,10, and 25 Pesos m/n that were seen being used had 12 sides). In any case, neither the old coins nor the new ones specified to what monetary value they belonged.

Source: El Telegrafo del Centro, Centro Numismatico, Buenos Aires, Ano 4, Numero 17, Diciembere, 1999.

Courtesy: Carlos Alberto Graziadio

|